Domestic Solar and other Generation in Northern Sweden

There are some weird opinions on the internet, and one common one regarding solar is that it’s not a good idea in places like northern Sweden. As someone living in with a solar installation in northern Sweden, this is always an odd belief to read; it’s not that dark, panels are cheap, and there’s good incentives for paying back to the grid.

There are three typical reasons to install solar power, two of which are do-able in northern Sweden:

- Financial: To get a financial return on your investment in the solar installation, from sold generation or reduced bills

- Environmental: to reduce your environmental impact by contributing to renewable energy production

- Resilience: to become non-dependent on the grid

Financial Return

Financial return is not a problem. A solar installation in Sweden is cheap (for example, 8-90000KR) compared to what I’ve seen quoted online in the USA. Installations break even in 9-12 years, depending on variables like the suitability of the site and mounting location. The panels come with a warranty for 15-30 years depending on the panel but will keep producing long after this. Panels do lose a tiny amount of efficiency each year, and it depends on the panel model, but modern panels will still be making electric at 75-80% of their original rate by the end of 30 years. The panels will eventually get replaced when the roof needs replacing. Generally the core cost consideration is the labour for the installation.

Environmental Impact

The environmental impact reduction is good. Solar panels are mostly glass and aluminium, with a small amount of rare materials. Studies generally agree that a solar panel breaks even for the environmental impact of their manufacture, after 1.5-2 years of production.

Resilience

Becoming year-round non-dependent on the grid using only solar would require lifestyle changes. Electrical heating and the cold temperatures and darkness of winter all combine to make an obstacle. As an example, our installation made 60kWh on the sunniest days in summer, and we consumed 45kWh on the coldest -30C day in winter – the problem in northern Sweden is that the two occur at opposite times of year and cant be compensated for using current domestic battery technology. With wood-fuelled heating and a cold cellar it would be possible but would not be fun and would be a labour-intensive home.

It is however possible to achieve smaller resilience targets like not being grid-dependent for 6-8 months of the year. Or achieving net-zero consumption for the year, by making more over an entire year than was sold to the grid.

Where should I put solar panels?

In our region, you don’t need planning permission for solar panels providing they follow the outline of the house. For example, flat on the roof or flat on the walls. There’s not much point having a sun tracking installation as the hardware is expensive. The same cost can be used to buy more panels. Moving machinery is also something that can break, freeze, or need maintenance.

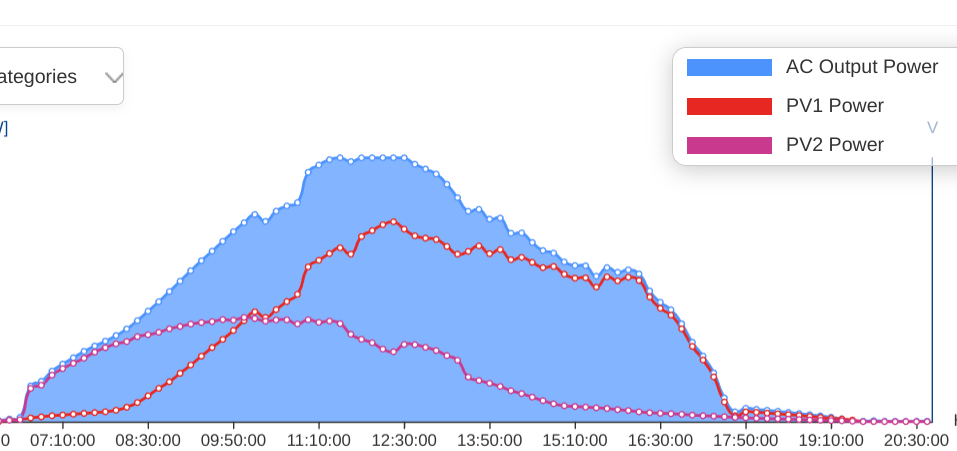

For maximum yearly output, a solar installer will typically recommend the optimal angle for yearly production and south-facing panels. Up north, lots of enthusiasts will suggest vertical panels, angled towards the winter sun. This way you make lots of electric when the hourly electric price is high in the spring. The vertical panels aren’t likely to accumulate snow, provided they are mounted at least a metre from ground level. Lastly, the rest of the year the panels make power early in the morning when the grid price typically spikes. The graph below for early April shows vertical panels (“PV2”) giving a long low output versus a larger array on a sloped roof (“PV1”). During early March the vertical panels outperform the roof. During summer, the roof panels far outproduce the vertical panels, but the electric prices are also much lower.

The vertical panels are also cheap to install, as the installer might not need an assistant or roof safety gear. Vertical panels also dump heat easier in a hot summer compared to panels on a low sloped roof.

A more general rule is to cover with solar panels any roof or wall that doesn’t face north. Especially where the panels won’t look ugly, and won’t upset the neighbours. Once you run out of locations, then think about ground mount solar or similar.

What is the most I can produce?

The most is limited by your fuse size to the grid – which is also your supply agreement.

For a standard 16 amp grid feed, you can send back to the grid a maximum of about 11kW continuous. In mid-May, a garage roof plus a house roof would likely easily meet that limit. A battery would be needed to time shift the overproduction. Hence, some bifacial vertical panels orientated east-west with a flatter generation profile might actually make more money for the same fuse size. For either, it’s sensible to have automation to cap the amount going to the grid to avoid blowing a fuse.

The maximum fuse size for a domestic connection with E.ON is 63 amps, which equates to about 43Kwh continuous. This is currently also the legal upper limit definition of a domestic feed in the tax agencies notes.

E.ON support said there is no restriction from themselves on what can make the power. So it can be from battery, wind, or microhydro etc.

What about wind power?

In summary, a wind turbine is a commitment. If you love mechanical things and turbines, then you’ll enjoy setting up and maintaining it. As a pure financial return, it’s better to go solar for nearly all sites, unless you absolutely need non-grid power.

The tower and turbine can be expensive and take ongoing maintenance. The same investment in solar panels will nearly always pay off sooner. But if you live near the top of a hill then you can be making power during the night, and in the winter when solar isn’t available.

Planning Permission for Wind

You don’t need planning permission, providing that the combined mast and the blade total height is below 10m tall. Another condition is that it must be at least the same distance from the property boundary as it is tall.

Higher than 10m or closer to a property line needs planning permission. The process might involve the council (kommune) checking if the neighbours want to veto the installation. Another warning is that any noise complaints from neighbours can result in having to take it down.

Wind Power Hardware

Larger than 10m will generate more power, so might be worth the request if you have few and far neighbours. There is a Swedish company, Innoventum, that makes wooden wind turbine towers starting at 12m tall and bigger.

For standard installations below 10m, look for a brand where people have tested the output, such as via YouTube. The istabreeze turbines are supposed to be good.

Don’t be tempted with roof-mount turbines. It will need planning permission, the roof cause detrimental turbulence, and there is a risk of noise transmitted through the roof structure. You instead ideally want to have an undeniably and constantly windy site, a high mast away from trees and houses, and the largest blade-swept area that doesn’t make loved ones afraid to go outside.

What about water power?

Any concrete works in a watercourse will need planning permission and are likely to be rejected. This because watercourses are important ecological systems that will be defended by the local council (kommune).

It might be possible to build something less efficient but lower impact and have it approved. However, you need the right property in terms of having a water course and bank that would work. You also need to think about what will happen in winter. Considerations include where the thick ice layers will form and where the free-flowing water level is underneath.

If you have the right conditions and could get approval, it would be a great source of power. Even something as small as 500 watts continuous will make a massive dent in any domestic electric bill.